Samuel Johnson's Literary Sphere

From the Journal of the Book Club of Washington

Spring 2013 VOL. 13 NO. 1

(Book Club of Washington web site: www.bookclubofwashington.org)

Book collections contain core materials. This article describes how this core can be

enhanced by a conceptual framework to guide our collecting interests.

•••••••••••••••••••

Trees, Roots, Branches, and Bromeliads 1

Thoughts on Book Collecting Foci

enhanced by a conceptual framework to guide our collecting interests.

•••••••••••••••••••

Trees, Roots, Branches, and Bromeliads 1

Thoughts on Book Collecting Foci

A book collection focused on the works of a single author can soon encounter dead ends and exhaust avenues of opportunity. In the case of Samuel Johnson, a few libraries – (among them, the Houghton Library at Harvard, the Huntington Library in Pasadena, and the British Library) – have all of the editions and much of the extant manuscript material related to Johnson’s major and minor publications. However, there are many other aspects related to a significant literary figure that can form satisfying, and perhaps unique, foci for a library and book collection.

The “roots” of an author’s primary works, the “branches” of his or her literary activities, and the “bromeliads,” or works of the author’s contemporaries or successors that were influenced by the author – all are potential areas for the entertainment and accumulations of the collector.

The Tree

The main trunks of the Samuel Johnson literary tree include, more or less chronologically, the poems London and The Vanity of Human Wishes and the (unsuccessful) dramatic tragedy Irene; the twice per week Rambler essays; the Dictionary of the English Language; the short novel The Prince of Abyssinia: A Tale, (later titled The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia); Johnson’s edition of The Plays of William Shakespeare; the Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland; and the Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, to the Works of the English Poets. 2

The “roots” of an author’s primary works, the “branches” of his or her literary activities, and the “bromeliads,” or works of the author’s contemporaries or successors that were influenced by the author – all are potential areas for the entertainment and accumulations of the collector.

The Tree

The main trunks of the Samuel Johnson literary tree include, more or less chronologically, the poems London and The Vanity of Human Wishes and the (unsuccessful) dramatic tragedy Irene; the twice per week Rambler essays; the Dictionary of the English Language; the short novel The Prince of Abyssinia: A Tale, (later titled The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia); Johnson’s edition of The Plays of William Shakespeare; the Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland; and the Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, to the Works of the English Poets. 2

Roots

All of these literary productions have the roots of their intellectual framework and style in Johnson’s education in the Latin and Greek classics, his exposure to his bookseller-father’s extensive inventory based on a purchase of a substantial private library, and his months at Pembroke College, Oxford.

In terms of material available to the collector in contemporary editions, his roots include: his favorite books 3; his co-authored multi-volume sale catalog for the Lord Harley library, perhaps the largest library in England; the associated Harleian Miscellany of Pamphlets and Tracts; and a book that greatly influenced Johnson’s religious outlook, Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life by William Law.

Other roots include the contemporary sources for the author’s major literary productions. In Johnson’s case these include:

- For the Rambler essays, selected works by Milton, Addison, Shakespeare, and Pope.

- For the Dictionary,

– Works, including Mandeville, Gower, Chaucer and Thomas More, on which Johnson’s prefatory material on the history of the English language was based.

- For Rasselas, Johnson’s 1735 translation from the French of Father Lobo’s Voyage to Abyssinia.

- For Johnson’s edition of The Works of Shakespeare, the First Folio, 4 and the notes of previous editors of Shakespeare, whose commentaries Johnson treated in even-handed variorum style in his edition – Rowe, Pope, Theobald, Hanmer, and Warburton.

- For the Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, later published as the Lives of the Poets, the works of the fifty-two poets and their biographers.

Chasing all of these Johnson roots would involve collecting the highlights of the several preceding centuries of English literature. Some selection of direction based on what tickles the collector’s fancy must be made.

The illustrative quotations in the Johnson Dictionary give some insight into the views and style of the quoted authors. One author that attracted my attention was the Earl of Clarendon, partly because his topic, the Cromwell (Scotch and Puritan) rebellion, in which Charles I lost his head with his crown, also relates to the roots of Johnson’s political outlook. 5 Here is the story of one root: Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion.

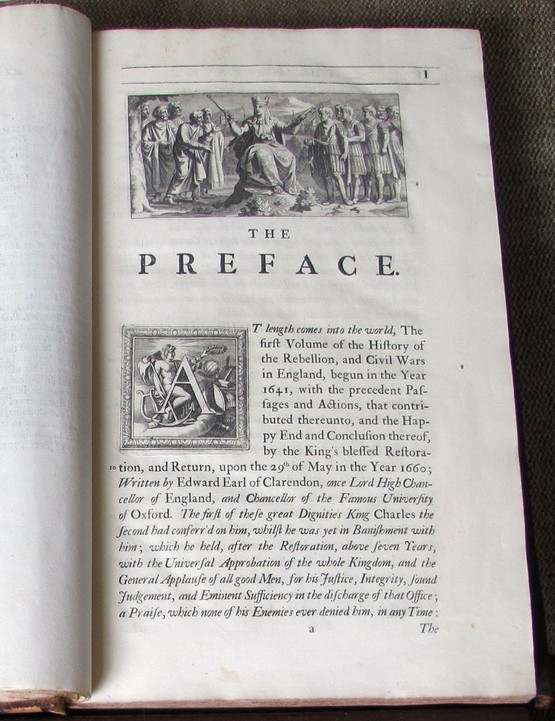

Collectible: The History of the Rebellion and the Civil Wars in England, begun in the year 1641, by Edward [Hyde] Earl of Clarendon, 3 vols., 1702-04, Oxford: Printed at the Theater. The boards measure 15 ½ by 10 inches; there are about six hundred pages in each volume with many high quality decorative engravings.

The first page of the Preface of Clarendon's History of the Rebellion

Clarendon’s life spanned the years 1604 to 1674. He initially opposed the King in the Long Parliament, but changed to the service of Charles I because of his strong ties to the Church of England. After the execution of Charles I, he was in exile with the future Charles II and James II, during Cromwell’s rule. He was an important official in the Charles II court after the 1660 restoration, and was appointed as the Chancellor of Oxford University. He was again in exile from the Charles II court because of foreign policy failures and after his daughter married the future James II – (and produced children while Charles II remained childless) – introducing doubts as to Clarendon’s loyalty to Charles II. Clarendon died in exile after writing memoirs, including the material for the History of the Rebellion in manuscript. His daughter Ann Hyde died before James II became King, but bore two daughters, Mary and Anne, who became Queens of England.

The History of the Rebellion was published by his son, after Clarendon’s death, from manuscripts. The tone of the Preface of the first volume reflects a continuing felt injury of the injustice to Clarendon by Charles II and his Court, even though a second Clarendon granddaughter, Anne, had just ascended to the throne at the time of publication in 1702.

Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion is quoted in Johnson’s Dictionary approximately eight hundred times, extending from “A” to “W.” The following examples may provide a flavor of Johnson’s dictionary definitions as well as Clarendon’s style and subject matter. 6

A’CCESSARY, adj. [A corruption, as it seems, of the word accessory, now more commonly used than the proper word]. That which, without being the chief constituent of a crime, contributes to it. But it had formerly a good and general sense.

“He had taken upon him the government of Hull, without any apprehension or imagination, that it would ever make him accessary to rebellion.” Clarendon b. viii

WORK. v.n. pret. 7 worked or wrought. [____8, Saxon, werken, Dutch]. 6. To operate, to have effect. 9 “These positive undertakings wrought upon many to think this opportunity should not be lost.” Clarendon

To WRE’STLE. v.n. [from wrest]. 2. To struggle, to contend: followed by with. “James knew not how to wrestle with desperate contingencies, and so abhorred to be entangled in such.” Clarendon

Boswell reports the following commentary by Johnson regarding Clarendon: “He is objected to for his parentheses, his involved clauses, and his want of harmony. It is … owing to a plethora of matter that his style is so faulty.” The profits from the sale of the several editions of the History of the Rebellion were assigned by Clarendon’s descendants to Oxford University and were used to enhance the University Press, which later received the name of the Clarendon Press.

Branches

The collateral activities of an author also frequently result in collectible material – whether assistance to friends and colleagues, commissioned material (ghost-written pieces or magazine contributions), or voluntary efforts for good causes. In Johnson’s case, these include, 10

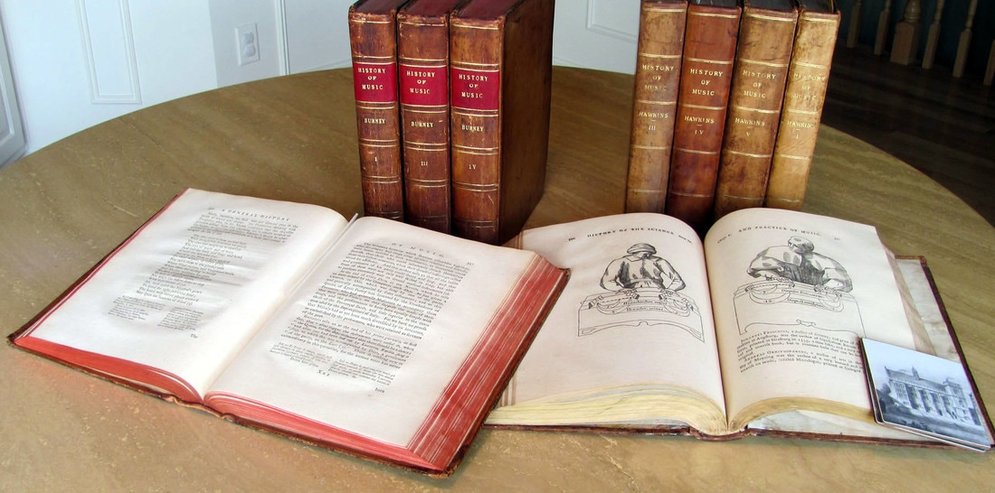

Collectible: A General History of Music, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period, by Charles Burney, Mus. Doc., F. R. S. Printed for the Author and sold by T. Becket, Strand; J. Robson, New Bond-Street; and J. Robinson, Paternoster-Row, 4 vols., 1776, 1782, 1789 (2 vols.).

Collectible: A General History of the Science and Practice of Music in Five Volumes, by Sir John Hawkins, London. Printed for T. Payne and Son at the Mews-Gate, (1776).

The collateral activities of an author also frequently result in collectible material – whether assistance to friends and colleagues, commissioned material (ghost-written pieces or magazine contributions), or voluntary efforts for good causes. In Johnson’s case, these include, 10

- Prefaces, Introductions and Dedications: those of most interest are those provided through friendship, such as dedication to the Queen for Burney’s History of Music and the dedication to the King for the Commemoration of Handel 11; preface for Charlotte Lennox’s Shakespeare Illustrated as well as several other pieces for Lennox; proposals and dedication for James’ Medical Dictionary 12; dedication for Spence’s Reliques of English Poetry; prologue written for David Garrick for the opening of the Drury Lane Theatre; dedication to the King for Joshua Reynold’s Seven Discourses; and many others written at the request of booksellers or publishers.13

- Contributions to the works of friends: lines for Goldsmith’s poem, “The Traveller 14;” contributions to Anna Williams’ 15 Miscellanies; a pamphlet written in the name of Zachariah Williams, Anna’s father, on An Account of an Attempt to ascertain the Longitude at Sea. 16

- Parliamentary Debates written for The Gentleman’s Magazine under the guise of “Debates in the Senate of Lilliput” based on notes taken by others

- Literary branches that did not result in contemporary collectible material include substantial assistance to William Chambers 18 in his Oxford law lectures and Johnson’s “end of patronage” letter to Chesterfield.

Collectible: A General History of Music, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period, by Charles Burney, Mus. Doc., F. R. S. Printed for the Author and sold by T. Becket, Strand; J. Robson, New Bond-Street; and J. Robinson, Paternoster-Row, 4 vols., 1776, 1782, 1789 (2 vols.).

Collectible: A General History of the Science and Practice of Music in Five Volumes, by Sir John Hawkins, London. Printed for T. Payne and Son at the Mews-Gate, (1776).

Burney’s A General History of Music, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period, with the Johnson translation of Euripides;

Hawkins’ A General History of the Science and Practice of Music in Five Volumes, with two of five cuts illustrating the use of the Monochord,

from Musica Theorica by Folianus, published in Venice in 1529.

Hawkins’ A General History of the Science and Practice of Music in Five Volumes, with two of five cuts illustrating the use of the Monochord,

from Musica Theorica by Folianus, published in Venice in 1529.

Charles Burney, a professional musician and a musicologist of extensive European travels, was a long time friend of Johnson’s dating from correspondence relating to Burney’s inquiry about copies of the soon to be published Dictionary. Burney’s family later welcomed Johnson into their home. Although Johnson consistently disclaimed any sensitivity to music, he attended concerts and listened to family musical performances.

It was natural for Burney to ask Johnson for assistance in writing the dedication to the Queen for the first volume of his History of Music. Johnson’s assistance in the dedication and in more extensive contributions to volume 2, published six years later, were not known to Burney’s contemporaries or to Johnson’s early biographers, Hawkins and Boswell. For the second volume, Johnson translated a poem by Euripedes from the Greek, wrote the apology at the end of the volume for Burney not completing the History in two volumes as the subscribers were promised, and also corrected many of the proof sheets for the volume.

Sir John Hawkins, whose acquaintance with Johnson predated Burney’s by a decade, was a lawyer and magistrate. He was also an avid amateur musician and musicologist. Both Burney and Hawkins were members of Johnson’s “Club,” but Hawkins withdrew, partly because he objected to sharing the dinner costs when he had earlier eaten at home. However, Hawkins’ relationship with Johnson continued and he was one of the executors of Johnson’s estate which gave him access to materials he used to write a Johnson biography and publish his works three years after Johnson’s death and four years before Boswell’s biography appeared.

In 1776, Hawkins’ five-volume History of Music was nearing publication. Burney learned of this and rushed his first volume into print to be first in the field. Burney also enlisted others to criticize in the press the Hawkins effort. Hawkins reputation as a musicologist did not survive the assault in the court of contemporary opinion.

Burney’s final two volumes did not appear until 1789, four years after Johnson’s death. The laurels must, in the end, be given to the amateur over the professional musician. A musician friend of mine, who was a respected conductor and music educator once told me that, during her college days, Hawkins was considered to be more accurate, but Burney more entertaining. 19

Johnson’s opinion of Hawkins’ History of Music was unknown to Hawkins, Burney, and Boswell. Johnson may not have looked at the Hawkins material until 1782, when he was assisting with Burney’s second volume. However, in that year, Johnson sent a five-volume set of Hawkins’ History of Music to Dr. Lawrence, who had been his physician. As part of a letter in Latin describing his medical condition, he wrote, “We have read scarcely anything more delightful or more copious.” 20

It was natural for Burney to ask Johnson for assistance in writing the dedication to the Queen for the first volume of his History of Music. Johnson’s assistance in the dedication and in more extensive contributions to volume 2, published six years later, were not known to Burney’s contemporaries or to Johnson’s early biographers, Hawkins and Boswell. For the second volume, Johnson translated a poem by Euripedes from the Greek, wrote the apology at the end of the volume for Burney not completing the History in two volumes as the subscribers were promised, and also corrected many of the proof sheets for the volume.

Sir John Hawkins, whose acquaintance with Johnson predated Burney’s by a decade, was a lawyer and magistrate. He was also an avid amateur musician and musicologist. Both Burney and Hawkins were members of Johnson’s “Club,” but Hawkins withdrew, partly because he objected to sharing the dinner costs when he had earlier eaten at home. However, Hawkins’ relationship with Johnson continued and he was one of the executors of Johnson’s estate which gave him access to materials he used to write a Johnson biography and publish his works three years after Johnson’s death and four years before Boswell’s biography appeared.

In 1776, Hawkins’ five-volume History of Music was nearing publication. Burney learned of this and rushed his first volume into print to be first in the field. Burney also enlisted others to criticize in the press the Hawkins effort. Hawkins reputation as a musicologist did not survive the assault in the court of contemporary opinion.

Burney’s final two volumes did not appear until 1789, four years after Johnson’s death. The laurels must, in the end, be given to the amateur over the professional musician. A musician friend of mine, who was a respected conductor and music educator once told me that, during her college days, Hawkins was considered to be more accurate, but Burney more entertaining. 19

Johnson’s opinion of Hawkins’ History of Music was unknown to Hawkins, Burney, and Boswell. Johnson may not have looked at the Hawkins material until 1782, when he was assisting with Burney’s second volume. However, in that year, Johnson sent a five-volume set of Hawkins’ History of Music to Dr. Lawrence, who had been his physician. As part of a letter in Latin describing his medical condition, he wrote, “We have read scarcely anything more delightful or more copious.” 20

Bromeliads

Other potential foci for a collection are works by others that were published because Johnson published. I have termed these “bromeliads” in my title. In Johnson’s case, bromeliads include: 21

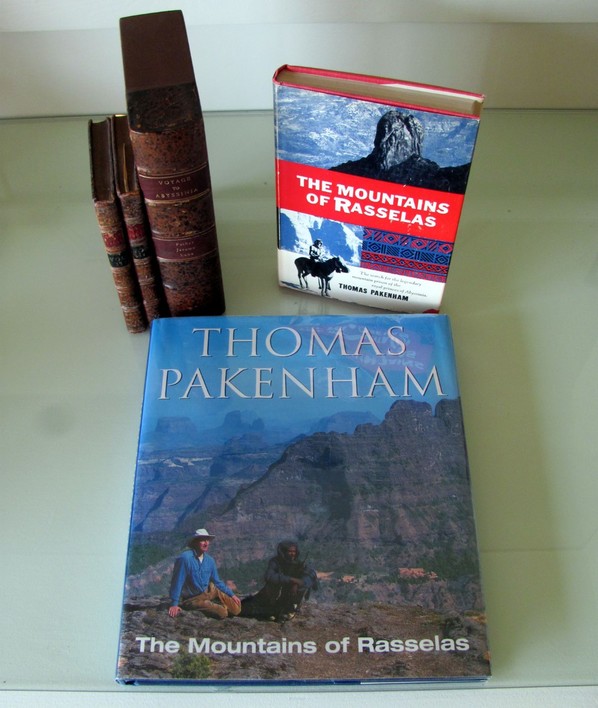

Johnson, in the opening of Rasselas likely had this setting in mind (from The Prince of Abyssinia, Chap. I, 1759): “According to the custom which has descended from age to age among the monarchs of the torrid zone, Rasselas was confined in a private palace, with the other sons and daughters of Abyssinian royalty, till the order of succession should call him to the throne.”

In 1958, a young man just out of Oxford decided to embark on adventurous travel, and chose the Johnson hint and information from other eighteenth century travels to Ethiopia 23 as the objective of his quest. He found that, in addition to the location referenced in the Voyage, there had been a prison in the north used before, and a prison in the south (described, but not seen by James Bruce) used after the mountain Guexen. After visiting all three sites, and getting to the top of two of the three, Thomas Pakenham on his return published a modestly popular book in the United Kingdom and the United States. Forty years later he repeated his itinerary, producing a coffee-table book (this time with color pictures from both trips) with text excerpts from his first book supplemented with his return observations. 24

Collectible: The Mountains of Rasselas, An Ethiopian Adventure by Thomas Pakenham, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 1959; Reynal & Company, New York, 1959; 192 pp. Cover subtitle: The search for the legendary mountain prison of the royal princes of Abyssinia.

Collectible: The Mountains of Rasselas, An Ethiopian Adventure by Thomas Pakenham, Text and Photos by Thomas Pakenham, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 1998; 171 pp.

Like many modern Johnson bromeliads, the Pakenham books are neither scarce nor common, and make a pleasing addition to a Johnson collection.

Other potential foci for a collection are works by others that were published because Johnson published. I have termed these “bromeliads” in my title. In Johnson’s case, bromeliads include: 21

- John Walker’s dedication of his Elements of Elocution to Johnson and the addition of pronunciation guides for each word in later editions of Johnson’s Dictionary.

- Chesterfield’s letters in The World – “puff” pieces – for Johnson’s Dictionary, after a long period of neglect following the dedication of the Plan of a Dictionary to Chesterfield.

- Women authors supported or encouraged by Johnson including Fanny Burney, Charlotte Lennox, Elizabeth Carter, Hannah More, and Hester Chapone.

- Over two hundred twentieth century academic or popular books about Samuel Johnson, most after 1950 – and several thousand articles in scholarly journals.

- Travel books based on Johnson’s trip to Scotland, and Pakenham’s travels to Ethiopia to explore the Mountains of Rasselas.

Johnson, in the opening of Rasselas likely had this setting in mind (from The Prince of Abyssinia, Chap. I, 1759): “According to the custom which has descended from age to age among the monarchs of the torrid zone, Rasselas was confined in a private palace, with the other sons and daughters of Abyssinian royalty, till the order of succession should call him to the throne.”

In 1958, a young man just out of Oxford decided to embark on adventurous travel, and chose the Johnson hint and information from other eighteenth century travels to Ethiopia 23 as the objective of his quest. He found that, in addition to the location referenced in the Voyage, there had been a prison in the north used before, and a prison in the south (described, but not seen by James Bruce) used after the mountain Guexen. After visiting all three sites, and getting to the top of two of the three, Thomas Pakenham on his return published a modestly popular book in the United Kingdom and the United States. Forty years later he repeated his itinerary, producing a coffee-table book (this time with color pictures from both trips) with text excerpts from his first book supplemented with his return observations. 24

Collectible: The Mountains of Rasselas, An Ethiopian Adventure by Thomas Pakenham, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 1959; Reynal & Company, New York, 1959; 192 pp. Cover subtitle: The search for the legendary mountain prison of the royal princes of Abyssinia.

Collectible: The Mountains of Rasselas, An Ethiopian Adventure by Thomas Pakenham, Text and Photos by Thomas Pakenham, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 1998; 171 pp.

Like many modern Johnson bromeliads, the Pakenham books are neither scarce nor common, and make a pleasing addition to a Johnson collection.

Pakenham’s two editions of the Mountains of Rasselas, with early editions of Rasselas and the Voyage to Abyssinia.

The conclusion, in which nothing is concluded

The title of the last chapter of Rasselas seems a good fit for this story as well. Like the choice of life, the choice of books for the collector has no one answer. My thesis is that our satisfaction in acquiring unusual and interesting artifacts can be enhanced by a conceptual framework to guide our collecting interests.

I have offered some thoughts on organizing a collection related to a single author and hope that these will lead to interesting conversations with collectors who organize their interests on broader themes.

notes

1. TREE: A large vegetable rising, with one woody stem, to a considerable height. ROOT: That part of the plant which rests in the ground, and supplies the stems with nourishment. BRANCH: The shoot of a tree from one of the main boughs. From Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson, A.M., 1755. BROMELIAD: Not in Johnson. The 1933 supplement to The Oxford English Dictionary notes the first use in 1866 in Treasures of Botany. Some of the bromeliads grow attached to the branches of trees and are called air plants. (A bromeliad is a type of Epiphyte, a plant which grows on another plant; usually restricted to those which derive only support and not nutrition from the plants upon which they grow.)

2. See the twenty-three volumes of the Yale Edition of the Works of Samuel Johnson. For an exhaustive listing of Johnson’s works, see A Bibliography of the works of Samuel Johnson, in two volumes, by J. D. Fleeman.

3. “No one ever wished a book longer, except Don Quixote, Robinson Crusoe, and Pilgrim’s Progress.” Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, Johnson said, was the only book that got him up earlier than he wished to rise.

4. “At first I collated the early folios, but afterward consulted only the first.” Shakespeare’s First Folio is not a feasible objective for most collectors; we must be satisfied with visiting some of the eighty copies (of about two hundred extant) in the Folger Shakespeare Library.

5. Johnson’s politics are difficult to categorize, and still generate interesting books.

6. The typeface of the folio Dictionary is very close to Garamond 11 font, except for the modern internal “s” rather than the long “ſ ” in use before the year 1800.

7. preterit = past tense

8. The Saxon letters are beyond my font-ability.

9. Clarendon’s is one of thirteen quotations that illustrate this sense.

10 Some additional branches include: sermons, most for his friend John Taylor and published under Taylor’s name posthumously; contributions to perceived good causes, both an unsuccessful appeal to the King for clemency and a final sermon for the condemned Dr. Dodd; the introduction for the Proceedings of the Committee for Cloathing French Prisoners; early satirical pamphlets against the government and later tracts written in support of the Government, most notably Taxation No Tyranny and Thoughts Respecting the Falkland Islands; and a number of book reviews and biographical sketches including contributions to The Gentleman’s Magazine and The Literary Magazine.

11. The last work prepared by Johnson for the press.

12. Johnson may also have contributed to a number of the entries in James’ Medical Dictionary.

13. Of the preface for Rolt’s Dictionary of Trade and Commerce, written at the request of the publisher, Johnson said he had never met the author or read the book, but knew very well what such a dictionary should be, so he wrote the preface describing the work as it should be.

14. The lines:

“How small, of all that human hearts endure,

The part that laws or kings can cause or cure.”

15. Anna Williams was one of Johnson’s household dependents, who was blind.

16. The government had offered a twenty thousand pound prize for a method to accurately determine the longitude.

17. Two of these debates, manufactured by Johnson only knowing the order of speakers and the side of the issue taken, appeared posthumously in The Works of Lord Chesterfield (but within Johnson’s lifetime) and were compared in the preface to the speeches of famous Roman orators.

18. Chambers followed Blackstone as Vinerian Professor of Law.

19. The entertaining and risqué story of a French Opera singer toward the end of volume 3 would not have survived a Johnson review of the proof sheets.

20. “vix quicquam vidimus aut suavius aut uberius.”

21. Other bromeliads include: Hester Thrale Piozzi (Anecdotes of Johnson, Letters to and from the Late Samuel Johnson, LL.D., British Synonymy); Malone and Steeven’s editions of Shakespeare, built on Johnson’s; Hawkins’ Life of Johnson and other early biographies; James Boswell’s Tour of the Hebrides and Life of Johnson, as well as subsequent editors of the life such as Crocker and Hill and of Boswell’s London Journal edited by Pottle; Dinarbus, a continuation of Rasselas by Ellis Cornelia Knight; numerous nineteenth and twentieth century pieces of ephemera from Johnson clubs, symposia, and exhibition catalogues; influence on later literary figures such as Jane Austen, Virginia Wolff, T. S. Eliot, and Samuel Beckett.

22. Guexen is now known as Amba Geshen.

23. Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, by James Bruce, published in 1790.

24. I was titillated (as have been other modern Johnsonians) by the mountain prison of the Voyage to Abyssinia. I found the Pakenham books in planning a trip to Ethiopia in 2009. My daughter and I reached Amba Geshen, high in the mountains, but accessible by foot, with an Orthodox monastery on the plateau next to the princes’ former encampment. I saw the other two prison locations at a distance.

The author is a mostly-retired engineer who has been collecting and reading Johnson material since reading John Wain’s biography Samuel Johnson, in 1974. He is a member of the Book Club of Washington and the Guild of Book Workers. He hopes readers will find the non-scholarly endnotes entertaining. These will not be on the test.

From the Journal of the Book Club of Washington

Spring 2013 VOL. 13 NO. 1